Intraductal papillomas of the breast

Introduction

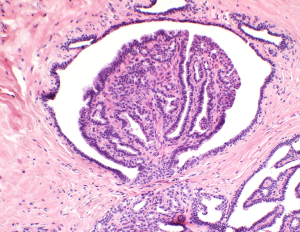

Papillary lesions of the breast were described as early as 1905 by J. Collins Warren (1). He described papillary lesions as benign or malignant. The distinction between the two can be a challenge to pathologists. Haagensen and colleagues described benign intraductal papillomas (IPs) as proliferations of duct epithelium which project outward into a dilated lumen (2) (Figures 1,2). They can have variable presentations depending upon their location in the breast, central versus peripheral. IPs are common breast lesions, however, historically the management of IPs has been controversial. This article will review the current literature with series published over the last 5 years regarding IPs with and without atypia and to summarize their management.

Presentation

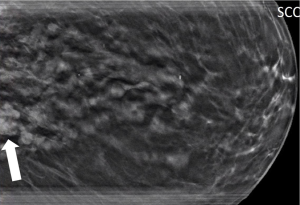

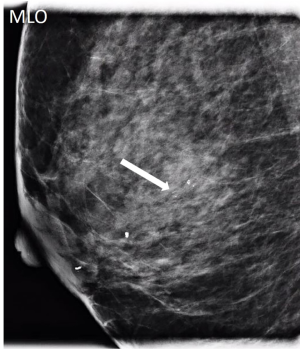

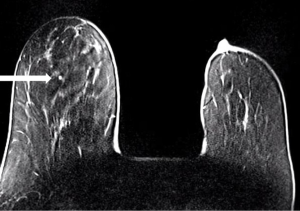

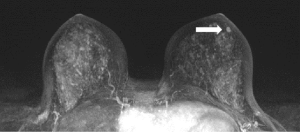

IPs can occur in women of all ages. With modern breast screening, asymptomatic IPs present as imaging findings on screening mammograms, ultrasounds or breast MRIs (3). Asymptomatic IPs are typically peripheral in location, present as calcifications or densities on mammograms or MRIs (Figures 3,4,5) and can have a higher association with malignancy (2,4).

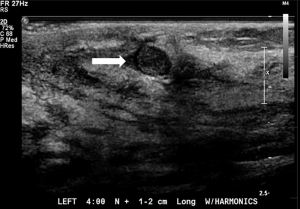

Symptomatic IPs typically occur in the large central ducts of the breast so they often present with serous or bloody nipple discharge (Figure 6). They can also present as palpable masses on clinical breast exam. They are typically solitary and tend to have a lower risk of carcinoma (2). Ultrasound usually demonstrates a solid intraductal mass (Figure 7) while mammographic findings can suggest a mass, density, or calcifications (3,5-7).

The diagnosis of papillary lesions provides a challenge to pathologists. The presence or absence of a myoepithelial cell layer in the papillary component of the lesion is the most important feature that helps differentiate a benign papilloma from a papillary carcinoma (8). IPs are typically diagnosed by stereotactic, ultrasound- or MRI-guided core needle biopsy (CNB) (9-11) or vacuum-assisted biopsy (12,13). Although minimally invasive techniques have become the gold standard in evaluating breast lesions, the findings can prove to be challenging to pathologists when trying to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions (12,14-16). Under sampling or sampling error can also lead to false negative rates after CNB therefore a sufficient amount of core samples is critical (17). The management of IPs, therefore, is dependent upon on the presence or absence of atypia and also on pathologic-radiologic concordance, the determination that clinical, imaging, and pathologic findings that are all in agreement (15).

Management

Intraductal papillomas with atypia

The general consensus for IPs with atypia diagnosed on CNB remains surgical excision to exclude malignancy. Upstaging rates to ductal carcinoma in situ or invasive carcinoma can range up to 77% (14,18-20).

Nakhlis and colleagues conducted a study in 2015 identifying 97 patients diagnosed with IPs on CNB; 52 IPs with atypia were identified and the remainder without atypia. Patient who had concomitant diagnoses of atypical ductal hyperplasia, ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or symptomatic nipple discharge were excluded from the study. All 97 patient underwent surgical excisions. Upstaging to carcinoma, all of which were DCIS, were found in 11 of 52 IPs with atypia for an upstage rate of 21% (21).

Hong et al. evaluated 592 papillary lesions diagnosed on CNB. 363 surgical excisions were performed and of those, 41 were IPs with atypia. Synchronous carcinomas and BIRADS 6 lesions were excluded. They found that 11 IPs with atypia were upstaged to carcinoma for an upgrade rate of 26.8%. Age >54, size >1 cm on ultrasound and a mammographic density were found to be statistically significant for upstaging to carcinoma. A trend was also seen in symptomatic patients with nipple discharge or palpable masses, however the trends were not statistically significant (16).

Armes et al. conducted a study in Australia evaluating 114 IPs diagnosed on CNB. A total of 103 excisions were performed for 36 IPs with atypia and 67 IPs without atypia. They divided the lesions into 2 groups: lesions associated with microcalcifications and lesions other than microcalcifications. In evaluating the IPs with atypia, malignancy was found in 1 of 8 (12.5%) lesions with microcalcifications whereas 25 of 28 (89%) lesions other than microcalcifications were upstaged to carcinoma for an overall upstage of 72%. They noted that pathologic-radiologic concordance through multidisciplinary review was important (14).

In 2018, Forester and colleagues performed a meta-analysis of high-risk lesions and reviewed 11 studies evaluating IPs with atypia. 91 malignancies were found in 298 lesions yielding a 31% upstaging rate to carcinoma (22). Similarly in 2013, Wen et al. conducted a meta-analysis of 34 studies in which a papillary lesion with atypia was diagnosed on CNB and found an upgrade rate to malignancy of 36.9% (23).

Kupsik, Perez and Bargaje identified 123 papillary lesions in their 2019 study. They evaluated patients diagnosed with papillary lesions on CNB and excluded any synchronous DCIS. These were divided into papillary lesions/papillomas, papillary lesion with hyperplasia and papillary lesion with atypia and 105 lesions underwent surgical excision within 6 months after diagnosis. They identified 47 IPs with atypia and 13 were upstaged to carcinoma for an upstage of 28%. They found that atypia in papillary lesions was the most significant contributor to the risk of upstaging to malignancy. They noted that atypical lesions demonstrated a higher likelihood of upstaging based on BI-RADS classification. Race, age, size of tumor and other radiographic features were not associated with an increased risk for upstaging to malignancy (18).

Finally, Liu et al. conducted a retrospective study in 2019 with the largest number of excisions discussed in this manuscript, excluding meta-analyses, for IPs with atypia. Out of 317 patients identified as having papillary lesions after CNB, 92 papillary lesions with atypia were identified, excluding 19 with atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH), atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH) or flat epithelial hyperplasia (FEA). 71 patients were upstaged to carcinoma for an upstage rate of 77%. They found that older patient age, larger lesion size >1 cm, and presence of atypia were factors associated with a higher risk of malignancy. They recommended excision for IPs with atypia and pathologic-radiologic discordance.

Based on these studies, we recommend surgical excision for IPs with atypia.

Intraductal papillomas without atypia

Making a definitive diagnosis for a papillary lesion based on a CNB remains a challenge for pathologists (15). Retrospective studies for IPs without atypia have shown upstaging rates to carcinoma ranging from 0–33% (24). Unlike IPs with atypia, for which the consensus is to undergo surgical excision due to higher rates of upstaging to carcinoma, there is no consensus for the management of IPs without atypia. Some studies have suggested a greater size, peripheral lesions, palpable masses, and lesions diagnosed in older patients carry a higher risk of upgrade (4,25-27). Until recently, it was a common recommendation for patients with IPs without atypia to undergo routine surgical excision. More recent studies are now suggesting otherwise.

In 2018, Ahn and colleagues evaluated 520 benign papillomas diagnosed on CNB. 452 were IPs without atypia; 250 of these lesions were excised within 6 months after diagnosis and 17 lesions were upstaged to carcinoma for a 6.8% upstaging rate. Multivariate analysis revealed that bloody nipple discharge, size on imaging ≥1.5 cm, BI-RADS ≥4b (which implies discordance), peripheral location >3 cm from the nipple and palpability were independent predictors of malignancy (28).

Chen et al. conducted a retrospective review in 2019 of 324 patients diagnosed with papillary lesions after CNB. Papillomas without atypia were found in 332 lesions, of which 265 underwent excisional biopsy. The upgrade to carcinoma was found in 6 patients for an upstage rate of 2.2%. Peripheral lesions in postmenopausal or older (P=0.001) patients showed significantly higher upgrade rates (29).

In 2019, Choi et al. reported on 500 patients diagnosed with IPs without atypia on CNB. 203 patients underwent surgical excision, 233 underwent ultrasound-guided directional vacuum-assisted removal (DVAR) with 8- and 11-gauge needles, depending on the size of the lesion, and 61 patients had no intervention but were followed with ultrasound for at least 2 years. Of the 206 patients who underwent surgical excision, DCIS was found in 4 patients for an upstage rate of 1.9%. In the DVAR group, 5 of 233 patients were upstaged to carcinoma for a rate of 2.1%, 4 being DCIS and 1 invasive ductal carcinoma. None of the 61 patients with no intervention were diagnosed with carcinoma during the time of the study and mean follow up of 43 months (30).

In their 2019 study, Liu and colleagues identified 317 papillary neoplasms after CNB that underwent surgical excision. 206 papillary lesions were identified with no atypia. Initially 7 patients were upstaged to malignancy for a rate of 3.4% however after a second pathology review, 2 cases were identified with no atypia after excluding the others with atypia for an upstage rate of 1%. They suggested serial imaging follow up for lesions less than 1 cm with no histological atypia and recommended attention to the size of the lesion identified (20).

Kuehner et al. identified 407 patients in a retrospective study presenting with a palpable mass diagnosed with IP without atypia on CNB. 327 patients underwent surgical excision, 61 patients underwent surveillance imaging, and 19 patients had no surgery nor imaging surveillance. Among the 327 women with surgical excision, 11 (3.4%) had in situ cancer and 8 (2.4%) had invasive cancer for an overall upstage rate of 5%. An upgrade to an in situ cancer or invasive cancer was more common among women with a lesion greater than 1 cm, a palpable breast mass, age >50 years, or if the lesion was >5 cm from the nipple, findings also supported by other studies (19-21,31,32). No cancers were diagnosed in 61 women followed by imaging surveillance followed for 2 years (26).

It must be noted that the majority of studies reported in the literature today are retrospective in nature which can lead to biases, however, the TBCRC 034 registry study done by Nakhlis et al. was a prospective multi-institutional registry to study the upgrade rate of IPs without atypia in a prospective manner, the first of its kind (33).

Intraductal papillomas with atypia and without atypia are summarized in Tables 1,2.

Table 1

| Study, year | Study design | Excisions (n) | Upgraded to carcinoma |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nakhlis, 2015 ( |

Retrospective | 52 | 11 (21%) |

| Hong, 2016 ( |

Retrospective | 41 | 11 (27%) |

| Armes, 2017 ( |

Retrospective | 36 | 26 (72%) |

| Forester, 2018 ( |

Meta-analysis | 298 | 91 (31%) |

| Kupsik, 2019 ( |

Retrospective | 47 | 13 (28%) |

| Liu, 2019 ( |

Retrospective | 111 | 76 (68%) |

Table 2

| Study, year | Study design | Excisions (n) | Upgraded to carcinoma |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ahn, 2018 ( |

Retrospective | 250 | 17 (7%) |

| Choi, 2019 ( |

Retrospective | 206 | 4 (2%) |

| Liu, 2019 ( |

Retrospective | 206 | 2 (1%) |

| Chen, 2019 ( |

Retrospective | 265 | 6 (2%) |

| Kuehner, 2019 ( |

Retrospective | 327 | 19 (5%) |

| Nakhlis, 2020 ( |

Prospective | 116 | 2 (1.7%) |

One hundred and sixteen patients were identified prospectively in the TBCRC 034 registry and consented to surgical excision after excluding discordant cases, BI-RADS >4, and those with concurrent lesions already requiring excision such as ADH or atypia. Masses or distortion were the most common imaging finding on mammogram in 77 patients, while mammographic calcifications were found in 25 patients. On MRI, 10 patients presented with masses and 4 patients with non-mass enhancement. Pathology review at the local institution upgraded 2 of 116 cases for an upstaging rate of 1.7%, both of which were DCIS. Both upgrades were diagnosed in patients on screening mammogram and MRI in masses less than 1cm in size. Interestingly, upon central pathology review of the slides in both upstaged cases, the central pathologist deemed both lesions represented ADH only and not DCIS. It was noted that in 1 of the 2 centrally reviewed cases, not all of the slides were available for central review so the highest possible rate of upstage could be 1.2% (33).

Lastly, it must be stressed that radiologic-pathologic concordance is critical when making recommendations for IPs without atypia (9,11,12,15,26,31). Some studies have reported concordance (16,31,33) whereas others have not (14,30,34). Sclerosing papillomas are well-defined solid masses on imaging (Figures 8,9) with a dominant sclerosed architecture, not to be confused with complex sclerosing lesions, which often appear as spiculated or stellate lesions on imaging (35). Pathologically they usually have wider, more collagenous fibrovascular cores (36). If a sclerosed papilloma is diagnosed on core needle biopsy and are found to be concordant with imaging, they do not require excision. When a lesion seen on imaging appears suspicious for carcinoma but CNB or VAB yields benign results, excision should be performed based on discordance.

Clinical scenarios

Scenario 1

A 53-year-old patient presents with an asymptomatic ovoid 1cm mammographic density diagnosed on a routine screening mammogram (Figure 3). Diagnostic imaging on ultrasound confirms a 0.7 cm intraductal lesion most consistent with an intraductal papilloma (Figure 7). Ultrasound guided core needle biopsy reveals an intraductal papilloma with no atypia which is deemed to be concordant by the radiologist. No surgical excision is recommended.

Scenario 2

A 64-year-old patient presents with a 2-month history of unilateral bloody nipple discharge (Figure 6). On clinical breast exam, she has reproducible bloody discharge emanating from a central duct with a 1.5 cm periareolar mass that can be appreciated near the areolar edge at 6:00. Mammogram revealed no abnormal findings but correlative ultrasound reveals a 1.5 cm intraductal mass (Figure 7). Ultrasound guided core needle biopsy reveals an intraductal papilloma with no atypia. Surgical excision is recommended given the patient’s presentation of nipple discharge with a palpable mass. Surgical pathology confirmed a 1.8 cm intraductal papilloma with no atypia. If the pathology would have revealed atypia, the patient would have been referred to the high-risk clinic for assessment and possible chemoprevention.

Scenario 3

A 71-year-old patient undergoes a routine screening mammogram which reveals a 5 mm grouping of calcifications in the retroareolar breast (Figure 4) confirmed on diagnostic mammogram. Stereotactic core needle biopsy reveals an intraductal papilloma with no atypia which is found to be concordant by the radiologist. No surgical excision is recommended.

Conclusion

To summarize, IPs with atypia should be excised due to the higher rate of upstaging to malignancy. Patients with IPs with atypia should also be referred for high risk assessment for possible chemoprevention. Surgical excision is not indicated for asymptomatic IPs without atypia where there is pathologic-radiographic concordance based on the prospective TBCRC 034 trial (33). Excision can be considered for those patients presenting with symptoms such as palpable masses, nipple discharge or larger masses greater than 1 cm.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Stephanie Chung and Dr. Ellen Morris for contributing their ultrasound and mammogram images, respectively.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Katharine Yao) for the series “A Practical Guide to Management of Benign Breast Disease. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/abs-20-113). The series “A Practical Guide to Management of Benign Breast Disease” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: Both authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Warren JC. The Surgeon and the Pathologist. JAMA 1905;XLV:149-65. [Crossref]

- Haagensen CD, Stout AP, Phillips JS. The papillary neoplasms of the breast. I. Benign intraductal papilloma. Ann Surg 1951;133:18-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brookes MJ, Bourke AG. Radiological appearances of papillary breast lesions. Clin Radiol 2008;63:1265-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kil WH, Cho EY, Kim JH, et al. Is surgical excision necessary in benign papillary lesions initially diagnosed at core biopsy? Breast 2008;17:258-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eiada R, Chong J, Kulkarni S, et al. Papillary lesions of the breast: MRI, ultrasound, and mammographic appearances. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012;198:264-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhu QL, Zhang J, Lai XJ, et al. Characterisation of breast papillary neoplasm on automated breast ultrasound. Br J Radiol 2013;86:20130215 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cabioglu N, Hunt KK, Singletary SE, et al. Surgical decision making and factors determining a diagnosis of breast carcinoma in women presenting with nipple discharge. J Am Coll Surg 2003;196:354-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tavassoli F. Papillary Lesions. Pathology of the Breast. Norwalk, Conn.: Appleton & Lange, 1992.

- Mercado CL, Hamele-Bena D, Oken SM, et al. Papillary lesions of the breast at percutaneous core-needle biopsy. Radiology 2006;238:801-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arora N, Hill C, Hoda SA, et al. Clinicopathologic features of papillary lesions on core needle biopsy of the breast predictive of malignancy. Am J Surg 2007;194:444-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Holley SO, Appleton CM, Farria DM, et al. Pathologic outcomes of nonmalignant papillary breast lesions diagnosed at imaging-guided core needle biopsy. Radiology 2012;265:379-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hodorowicz-Zaniewska D, Siarkiewicz B, Brzuszkiewicz K, et al. Underestimation of breast cancer in intraductal papillomas treated with vacuum-assisted core needle biopsy. Ginekol Pol 2019;90:122-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seely JM, Verma R, Kielar A, et al. Benign Papillomas of the Breast Diagnosed on Large-Gauge Vacuum Biopsy compared with 14 Gauge Core Needle Biopsy - Do they require surgical excision? Breast J 2017;23:146-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Armes JE, Galbraith C, Gray J, et al. The outcome of papillary lesions of the breast diagnosed by standard core needle biopsy within a BreastScreen Australia service. Pathology 2017;49:267-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Collins LC, Schnitt SJ. Papillary lesions of the breast: selected diagnostic and management issues. Histopathology 2008;52:20-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hong YR, Song BJ, Jung SS, et al. Predictive Factors for Upgrading Patients with Benign Breast Papillary Lesions Using a Core Needle Biopsy. J Breast Cancer 2016;19:410-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jackman RJ, Nowels KW, Rodriguez-Soto J, et al. Stereotactic, automated, large-core needle biopsy of nonpalpable breast lesions: false-negative and histologic underestimation rates after long-term follow-up. Radiology 1999;210:799-805. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kupsik M, Perez C, Bargaje A. Upstaging papillary lesions to carcinoma on surgical excision is not impacted by patient race. Breast Dis 2019;38:67-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakhlis F. How Do We Approach Benign Proliferative Lesions? Curr Oncol Rep 2018;20:34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu C, Sidhu R, Ostry A, et al. Risk of malignancy in papillary neoplasms of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2019;178:87-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakhlis F, Ahmadiyeh N, Lester S, et al. Papilloma on core biopsy: excision vs. observation. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:1479-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Forester ND, Lowes S, Mitchell E, et al. High risk (B3) breast lesions: What is the incidence of malignancy for individual lesion subtypes? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol 2019;45:519-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wen X, Cheng W. Nonmalignant breast papillary lesions at core-needle biopsy: a meta-analysis of underestimation and influencing factors. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:94-101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grimm LJ, Bookhout CE, Bentley RC, et al. Concordant, non-atypical breast papillomas do not require surgical excision: A 10-year multi-institution study and review of the literature. Clin Imaging 2018;51:180-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen YA, Mack JA, Karamchandani DM, et al. Excision recommended in high-risk patients: Revisiting the diagnosis of papilloma on core biopsy in the context of patient risk. Breast J 2019;25:232-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuehner G, Darbinian J, Habel L, et al. Benign Papillary Breast Mass Lesions: Favorable Outcomes with Surgical Excision or Imaging Surveillance. Ann Surg Oncol 2019;26:1695-703. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shouhed D, Amersi FF, Spurrier R, et al. Intraductal papillary lesions of the breast: clinical and pathological correlation. Am Surg 2012;78:1161-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahn SK, Han W, Moon HG, et al. Management of benign papilloma without atypia diagnosed at ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy: Scoring system for predicting malignancy. Eur J Surg Oncol 2018;44:53-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen P, Zhou D, Wang C, et al. Treatment and Outcome of 341 Papillary Breast Lesions. World J Surg 2019;43:2477-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choi HY, Kim SM, Jang M, et al. Benign Breast Papilloma without Atypia: Outcomes of Surgical Excision versus US-guided Directional Vacuum-assisted Removal or US Follow-up. Radiology 2019;293:72-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pareja F, Corben AD, Brennan SB, et al. Breast intraductal papillomas without atypia in radiologic-pathologic concordant core-needle biopsies: Rate of upgrade to carcinoma at excision. Cancer 2016;122:2819-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boufelli G, Giannotti MA, Ruiz CA, et al. Papillomas of the breast: factors associated with underestimation. Eur J Cancer Prev 2018;27:310-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakhlis F, Baker GM, Pilewskie M, et al. The Incidence of Adjacent Synchronous Invasive Carcinoma and/or Ductal Carcinoma In Situ in Patients with Intraductal Papilloma without Atypia on Core Biopsy: Results from a Prospective Multi-Institutional Registry (TBCRC 034). Ann Surg Oncol 2021;28:2573-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khan S, Diaz A, Archer KJ, et al. Papillary lesions of the breast: To excise or observe? Breast J 2018;24:350-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Loane J. Benign sclerosing lesions of the breast. Diagn Histopathol (Oxf) 2009;15:395-401. [Crossref]

- Saad RS, Kanbour-Shakir A, Syed A, et al. Sclerosing papillary lesion of the breast: a diagnostic pitfall for malignancy in fine needle aspiration biopsy. Diagn Cytopathol 2006;34:114-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Calvillo KZ, Portnow LH. Intraductal papillomas of the breast. Ann Breast Surg 2021;5:24.