Defining skin-sparing mastectomy surgical techniques: a narrative review

Introduction

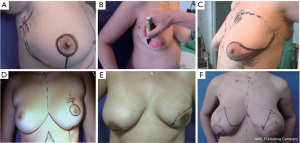

Evolution

In 1991, the term “skin-sparing mastectomy” (SSM) was coined by Toth and Lappert; a technique that facilitated immediate reconstruction due to the advantages given by preservation of the uninvolved breast skin and of the inframammary fold. Toth and Kroll et al. published their experience using the same technique (1,2). This sparked a discussion on the balance between cosmetic results and local disease control. The story began earlier with Barton et al., who tested the hypothesis that SSM would have residual glandular tissue but found similar rates of glandular residue between prophylactic and therapeutic mastectomies (3). The era of SSM began with these concepts and post-mastectomy breast reconstructions (Figure 1) (1-3).

Definition

SSM is a surgical technique that involves making minimal incisions while preserving the widest possible coverage and the subcutaneous breast groove, aiming to remove any previous excision scars, or scarring caused by any diagnostic procedures. The same incision can be used to access the axilla for axillary dissection or sentinel-node biopsy. Additional incisions may be required to perform reconstructive procedures such as microsurgical axillary anastomosis (1,4,5). An added layer of complexity involves preserving the underlying subdermal plexus, which supplies the overlying breast skin, a crucial parameter for mastectomy skin flap survival. Failure to preserve this can result in skin flap necrosis and infection, leading to further complications such as implant loss if implants are used, or further operations for debridement and resurfacing. Some authors consider nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM) a total SSM (6). Table 1 shows the difference between SSM with other types of mastectomies and their related procedures to clarify the difference between each type’s definition (6-8).

Table 1

| Mastectomy type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Halstead/radical mastectomy | Remove the whole breast plus pectoralis major and minor muscles and axillary lymph nodes through a large oblique incision reaching the axillary fossa |

| Modified radical mastectomy | Removes the breast plus axillary lymph nodes (level I and II) but preserves the pectoralis muscles |

| Total/simple mastectomy | Remove the breast, including a large ellipse of skin, nipple, and areola, without axillary dissection |

| SSM | The breast, nipple, and areola are removed while the remaining breast skin is preserved |

| NSM or total SSM | This surgery involves removing the breast while preserving the skin, nipple, and areola |

| Quadrantectomy | This procedure involves the excision of a quadrant of breast tissue containing the disease, including skin and pectoralis fascia |

| Lumpectomy | This involves the excision of a segment of breast tissue with the disease, without skin or muscle. It is also known as partial or segmental mastectomy and BCS |

| Oncoplastic surgery | This procedure involves the excision of breast tissue with disease and techniques to reshape or rearrange the remaining glandular tissue |

| Axillary node dissection | This surgery involves the removal of level I (inferior and lateral to pectoralis minor) and level II (posterior to pectoralis minor) axillary lymph nodes |

| Sentinel lymph node biopsy | This procedure involves the removal of the first few axillary nodes that drain the breast, which is identified by dual mapping using technetium-99m sulfur colloid and blue dye |

SSM, skin-sparing mastectomy; NSM, nipple-sparing mastectomy; BCS, breast conserving surgery.

Classification

There are five different types of SSMs, which are summarized in Table 2 and Figure 2 (1,5,9,10).

Table 2

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Resection of breast skin around the NAC |

| II | Resection of the NAC with medial or lateral extension and the removal of previous biopsy scars |

| III | NAC peri-areolar resection and incision to remove previous biopsy scars |

| IV | Elliptical resection of skin wider than before, including the NAC, to reduce ptosis. This is recommended for ptotic and hypertrophic breasts |

| V | Resection of skin and chest wall with an inverted T pattern is also indicated for ptotic and hypertrophic breasts |

SSM, skin-sparing mastectomy; NAC, nipple-areola complex.

Indications and oncological safety of SSM

The indications for SSM include ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), stage I–II infiltrating breast carcinomas, and local recurrences after conservative treatment (9). As stipulated by the 2023 US National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, SSM and NSM are safe for patients with early-stage, biologically favorable invasive breast cancer or DCIS; imaging results indicate no nipple or skin involvement, clear nipple margins, and no nipple discharge or Paget’s disease (11-15). Several studies have demonstrated that SSM is associated with similar rates of local recurrence when compared to non-SSM interventions, with lower rates of distant relapse. A 2010 meta-analysis of nine studies, published between 1997 and 2009, comprising 3,739 patients, revealed no significant differences in the rates of local recurrence between SSM and non-SSM patients. However, the SSM group exhibited a lower percentage of distant relapses compared to the non-SSM group (16). Another meta-analysis of 20 studies involving 5,594 women with early-stage breast cancer found no differences in oncologic outcomes between SSM and conventional mastectomy without reconstruction (17). The data indicates that NSM and SSM are safe from an oncological perspective, provided that the indications are respected. The indications for conservative mastectomy may expand in the future, including patients after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. However, complications may be more frequent in these cases (17,18). In conclusion, SSM is an appropriate surgical option for patients with DCIS or stage I–II infiltrating breast carcinomas and some selected cases of stage III. However, patients with inflammatory or locally advanced carcinomas or smokers are less suitable candidates for SSM, with smoking being a relative contraindication requiring adaptation of the surgical technique (9). We present this article in accordance with the Narrative Review reporting checklist (available at https://abs.amegroups.org/article/view/10.21037/abs-23-19/rc).

Methods

Two independent authors searched for relevant studies on Medline (via PubMed), Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Google Scholar, Clinical Trials and Embase databases from January 1901 to February 2023. The search terms consisted of “skin-sparing mastectomy”, “surgical techniques”, “mastectomy”, “mastectomy techniques”, “mastectomy surgery”, “breast cancer surgery”, and “surgical oncology. The search strategy for PubMed was ((“Skin-Sparing Mastectomy”[Title/Abstract] OR “Mastectomy, Skin Sparing”[Title/Abstract] OR “Skin Sparing Surgery”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“Surgical Techniques”[Title/Abstract] OR “Mastectomy Techniques”[Title/Abstract] OR “Breast Cancer Surgical Techniques”[Title/Abstract] OR “Mastectomy Surgical Procedure”[Title/Abstract])). Additionally, the reference lists of previous reviews and relevant articles were manually checked.

Discussion

SSM surgical techniques

To achieve favorable results with minimal complications, it is important to consider the basic elements of this procedure. The initial step is to tailor the incision based on the presence or absence of scars from previous excisions, along with breast size and sagging (Figure 2) (1,5,9,10).

Type I SSM involves the creation of a 5mm or longer peri-areolar incision, with an optional second transverse incision in the axilla for axillary dissection or microsurgical anastomosis (1,5,9,10). In some cases, it may be necessary to extend the peri-areolar incision towards the axillar or 6 o’clock position to facilitate reconstruction (1,5,9,10). Conversely, type II SSM involves incorporating the existing scar and designing the incision accordingly to ensure continuity with the previous scar (1,5,9,10). Type III SSM involves the design of separate incisions for nipple-areola complex (NAC) removal and previous scars to create a “bridge” between the two skin margins, thereby preventing any potential loss of vitality that could result from overlapping (1,5,9,10). Types IV and V are utilized for sagging or ptotic breasts, where the goal is to correct any asymmetry with the contralateral breast. This can be accomplished via elliptical skin resection or incision methods, including the inverted “T” resection on both sides of the NAC (1,5,9,10).

In addition to Carlson’s well-described incision patterns, other authors have used different patterns (6). One example is the Hall-Findlay vertical reduction mammaplasty pattern, founded by Claude Lassus and Madeleine Lejour, which has recently been used for SSM with autologous immediate based reconstruction (IBR), such as latissimus dorsi (LD) and deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flaps (19). Some authors have also described endoscopic or video-assisted SSM with either IBR or LD flap-based IBR, using a lower axillary incision of 5–6 cm after sentinel lymph node biopsy or level I/II dissection through the same incision (20-23). Another instance is the Double Asymmetric Circular Incision, a new immediate breast reconstruction technique that appeared to be safe and easily reproducible in patients with small to medium-sized breasts and with little to moderate ptosis (24). The combination of SSM with free NAC transplantation is another increasingly popular surgical technique, which involves the removal of the NAC and reattaching it in a different location in a single operation, and reportedly boasts greater cosmetic quality than a secondary reconstruction.

A comprehensive explanation is necessary for the mastectomy flaps that have been dissected, as they are important for both the oncological and postoperative well-being aspects of the surgery. To prevent any damage with spacers, the dissection process must be accurate, and the flaps should have a uniform thickness. Flaps that are too thin do not improve oncological safety and have a higher probability of causing skin necrosis (25). According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, one randomized control trial has demonstrated the use of prophylactic topical 2% nitroglycerine to reduce mastectomy skin flap necrosis in both SSM and NSM (11-15).

Regarding anatomical differences among individuals, only 56% have a superficial layer of the superficial fascia that aids in dissection. The remaining 44% pose a challenge when using this surgical approach. Moreover, in both cases, a mammary gland may be located near the dermis, making it very challenging to remove all the breast tissue without damaging the flaps (26).

In the operating room, the surgeon needs to have the excised tissue evaluated by a pathologist to determine its positioning and conduct mammography, particularly in the breast tissue surrounding the tumor, to ensure no disease remains. If any disease is discovered, the surgeon must increase the amount of cutaneous resection. This assessment is especially critical for in situ carcinomas and can decrease the chances of local recurrence (27).

The four main techniques utilized for breast reconstruction include the transverse rectus abdominis muscle (TRAM) flap, a free microsurgical flap like the DIEP flap, anatomical expanders (temporary or permanent) with direct implants-less often recommended, and an extended LD flap or LD flap placed over an implant or expander (9).

Preservation of the underlying vasculature is paramount in mastectomies. Several studies have shown that the blood supply to the breast derives from the external and internal mammary arteries, the intercostal and thoraco-acromial arteries (28). Some authors therefore propose using lateral incisions, avoiding peri-areolar incisions due to increased skin traction, and limiting dissection to maintain the skin flap’s blood supply during mastectomies. Dissection using scissors with only point cauterization is also recommended to minimize the risk of thermal injury to the skin flaps (29). Others assert that while inframammary incisions offer more aesthetically pleasing scar outcomes, it may potentially compromise the inframammary vasculature (30). This assertion is evidenced by Proano and Perbeck’s study involving a cohort of 69 patients, where they discerned a substantial diminution in blood flow to an area 2 cm below the NAC in the group subjected to the inframammary approach (31). The boundaries of the dissection should be clearly understood by the oncologic surgeon. Most sources concur that to preserve as many feeding vessels as possible, skin flaps should be elevated to, but never exceed, the clavicle superiorly, the anterior axillary line laterally, or over the sternum medially (32). Dissection inferiorly should never transgress the inframammary fold. This tenuous region is devascularized even further when the inframammary fold needs to be recreated through the placement of deep sutures.

SSM complications and modifiable risk factors associated with complications

SSM can lead to several complications, such as infection, hematoma, and skin flap necrosis. Various factors increase the risk of skin flap necrosis, such as smoking, previous or adjuvant breast irradiation, diabetes, and a high body mass index (33). Prior research has shown that traditional mastectomies result in flap necrosis in 5.6–8% of cases, compared to 3–15% in SSM, varying according to the series examined (33,34). According to Sbitany et al., meticulous patient selection and surgical method optimization resulted in a surprisingly low flap necrosis rate (5.6%) (35).

Preventing necrosis in mastectomy flaps is crucial to ensure a satisfactory cosmetic outcome, particularly if an expander or implant is used for reconstruction. This complication can lead to implant extrusion and procedure failure (9). Avoiding necrosis requires careful preparation of the mastectomy flaps, including ensuring they are uniformly thick to prevent devitalization (9). Where there is extensive skin necrosis or necrosis with evidence of infection, surgical debridement and exploration may be necessary to prevent implant loss, regardless of whether muscular coverage was provided or not (9).

Assessing a patient’s smoking status is crucial to reduce the risk of necrosis due to its vasoconstrictive property affecting the skin (9). Additionally, it indirectly inhibits the release of catecholamines, which can reduce the production of capillary flow. Therefore, being a non-smoker is preferred (although smoking is only a relative contraindication) to reduce the risk of necrosis (9).

The planning and results of surgery are also affected by radiotherapy in many ways. If done before surgery, it may harm the final cosmetic outcome and raise the risk of problems like skin flap necrosis and wound breakdown (35). When used as an adjuvant treatment or for a local recurrence, it can also negatively impact the cosmetic result, depending on the reconstructive technique used (35). In general, when patients have previously undergone radiation and SSM, reconstructive techniques such as DIEP and TRAM flaps are preferred to improve outcomes and preserve skin to prevent necrosis. These procedures can help maintain cosmetic results (9,35).

Cosmetic outcome

The aesthetic benefits of SSM are difficult to examine scientifically. Still, we agree with other authors that this technique can improve the results of breast reconstruction by preserving the sub-mammary tissue and skin coverage (35-37). Previous research has shown that SSM can positively impact reconstruction outcomes, including correcting symmetry (35-37). For example, a study comparing TRAM flap with expander reconstructions, with and without SSM, found that a higher percentage of cases with SSM did not require correction of the contralateral breast (38). We believe that the procedure results demonstrate the best evidence for the aesthetic advantages of SSM in terms of reconstruction and symmetry.

Ideal time for reconstructions: immediate or delayed

Overview

The optimal timing and technique for breast reconstruction involves careful consideration of each patient’s unique circumstances and potential complications and risk (39). Breast reconstruction options include immediate reconstruction (performed simultaneously with mastectomy), delayed reconstruction (performed after completion of adjuvant treatment), and delayed-immediate reconstruction (involving tissue expansion during mastectomy and final reconstruction after adjuvant treatment) (39). A recent meta-analysis of 30 studies, involving approximately 14,000 patients, compared immediate and delayed reconstruction approaches and found that patients undergoing immediate reconstruction experienced more surgical complications, seroma, and infection. However, after conducting a sensitivity analysis on the subset of patients receiving post-mastectomy irradiation, no significant differences were found between the two groups (40). The advantages and contraindications of the immediate reconstruction approach are summarized in Table 3 (41).

Table 3

| Advantages | Contraindications (relative) |

|---|---|

| No extra scars | Chest wall or skin infiltration by aggressive tumors |

| Single surgery | Previous irradiation |

| Positive psychological outcomes | Smoking |

| Similar color, texture, and sensation of the skin flaps | Severe breast hypertrophy or morbid obesity |

| Rapid recovery | Psychological disorders which impact patient expectations and understanding |

Challenges and strategies for selecting the optimal timing and technique for breast reconstructive surgery

When considering breast reconstruction, various factors must be taken into account, such as cancer stage, tumor size and location, smoking status, axillary lymph node status, previous surgeries and radiotherapy, chemotherapy, pre-existing medical conditions, and patient preference (42,43). The primary concern with immediate breast reconstruction is the uncertainty of post-mastectomy radiotherapy, which can lead to significant risks and complications (42,44). Patients with stage I breast cancer, a favorable prognosis, a negative sentinel lymph node, and no requirement for axillary lymphadenectomy surgery or radiotherapy are typically advised to undergo immediate breast reconstruction (42). However, patients with stage II and III breast cancer are at high risk for postmastectomy radiotherapy and should undergo delayed or delayed-immediate breast reconstruction, per current guidelines (42). Despite this, some stage II patients may be able to receive immediate breast reconstruction if preoperative assessments, such as sentinel lymph node biopsy, are performed to more accurately determine their radiotherapy needs (45,46). There is controversy about whether to suggest radiotherapy based on the number of positive lymph nodes, given that a positive sentinel lymph node may be the only one identified in 85% of patients (45,47). Although these assessment methods are available, the necessity for radiotherapy can only be confirmed following conclusive pathological examination since the degree of tumor infiltration in the breast tissue is also a crucial factor (42).

Delayed-immediate reconstruction approach

In 2004, MD Anderson Cancer Center proposed a protocol for breast reconstruction and radiotherapy known as the “delayed-immediate reconstruction” for patients who may require radiotherapy following the final pathological examination (48). This protocol is primarily intended for patients with stage II breast cancer, one or more positive lymph nodes on biopsy, visible microcalcifications on mammography, and/or apparent multicentricity on ultrasonography (42,47). The delayed-immediate approach involves a SSM, followed by the placement of an expander in the subpectoral pocket (42,48). During radiotherapy, this expander is deflated and then expanded once more. Following tissue expansion, there is a waiting period of 4–6 months, after which breast reconstruction using an autologous flap and, if local conditions are acceptable, occasionally with a final implant, is performed (42,48). This protocol preserves the skin envelope and reduces complication rates from 38% for traditional delayed flap reconstruction to 26% for delayed-immediate reconstruction with an autologous flap (42,48). Furthermore, if the final pathological examination indicates that radiotherapy is unnecessary, a definitive breast implant can be inserted within a well-preserved skin envelope after tissue expansion (42,48,49).

Conclusions

SSM is a surgical procedure that has demonstrated favorable aesthetic results while providing optimal local cancer control; however, certain criteria must be met to ensure safety and efficacy. These criteria encompass the need for an experienced surgical team, a multidisciplinary evaluation process, the identification of suitable candidates, and the achievement of adequate margins. The procedure entails careful selection of the incision site and type, preservation of the cutaneous pocket and sub-mammary fold, and may lead to superior cosmetic outcomes. Additionally, this approach allows for immediate reconstruction following SSM which may decrease the need for additional reconstructive procedures.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at https://abs.amegroups.org/article/view/10.21037/abs-23-19/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://abs.amegroups.org/article/view/10.21037/abs-23-19/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://abs.amegroups.org/article/view/10.21037/abs-23-19/coif). W.M.R. serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Annals of Breast Surgery from December 2023 to November 2025. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Toth BA, Lappert P. Modified skin incisions for mastectomy: the need for plastic surgical input in preoperative planning. Plast Reconstr Surg 1991;87:1048-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kroll SS, Ames F, Singletary SE, et al. The oncologic risks of skin preservation at mastectomy when combined with immediate reconstruction of the breast. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1991;172:17-20. [PubMed]

- Barton FE Jr, English JM, Kingsley WB, et al. Glandular excision in total glandular mastectomy and modified radical mastectomy: a comparison. Plast Reconstr Surg 1991;88:389-92; discussion 393-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moran SL, Serletti JM, Fox I. Immediate free TRAM reconstruction in lumpectomy and radiation failure patients. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000;106:1527-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carlson GW, Bostwick J 3rd, Styblo TM, et al. Skin-sparing mastectomy. Oncologic and reconstructive considerations. Ann Surg. 1997;225:570-5; discussion 575-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cil TD, McCready D. Modern Approaches to the Surgical Management of Malignant Breast Disease: The Role of Breast Conservation, Complete Mastectomy, Skin- and Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy. Clin Plast Surg 2018;45:1-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Veronesi U, Saccozzi R, Del Vecchio M, et al. Comparing radical mastectomy with quadrantectomy, axillary dissection, and radiotherapy in patients with small cancers of the breast. N Engl J Med 1981;305:6-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tenofsky PL, Dowell P, Topalovski T, et al. Surgical, oncologic, and cosmetic differences between oncoplastic and nononcoplastic breast conserving surgery in breast cancer patients. Am J Surg 2014;207:398-402; discussion 402. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- González EG, Rancati AO. Skin-sparing mastectomy. Gland Surg 2015;4:541-53. [PubMed]

- Hammond DC, Capraro PA, Ozolins EB, et al. Use of a skin-sparing reduction pattern to create a combination skin-muscle flap pocket in immediate breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002;110:206-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clarke M, Collins R, Darby S, et al. Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 2005;366:2087-106. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arriagada R, Lê MG, Rochard F, et al. Conservative treatment versus mastectomy in early breast cancer: patterns of failure with 15 years of follow-up data. Institut Gustave-Roussy Breast Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol 1996;14:1558-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1233-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials. Lancet 2011;378:1707-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jahan S, Al-Saigul AM, Abdelgadir MH. Breast cancer. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of breast self examination among women in Qassim region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 2006;27:1737-41. [PubMed]

- Simmons RM, Fish SK, Gayle L, et al. Local and distant recurrence rates in skin-sparing mastectomies compared with non-skin-sparing mastectomies. Ann Surg Oncol 1999;6:676-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Santoro S, Loreti A, Cavaliere F, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is not a contraindication for nipple sparing mastectomy. Breast 2015;24:661-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Frey JD, Choi M, Karp NS. The Effect of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Compared to Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Healing after Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2017;139:10e-9e. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Serra MP, Staley H. The Hall-Findlay mammaplasty pattern for skin-sparing mastectomy: case report. G Chir 2012;33:14-6. [PubMed]

- Ito K, Kanai T, Gomi K, et al. Endoscopic-assisted skin-sparing mastectomy combined with sentinel node biopsy. ANZ J Surg 2008;78:894-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ho WS, Ying SY, Chan AC. Endoscopic-assisted subcutaneous mastectomy and axillary dissection with immediate mammary prosthesis reconstruction for early breast cancer. Surg Endosc 2002;16:302-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kitamura K, Ishida M, Inoue H, et al. Early results of an endoscope-assisted subcutaneous mastectomy and reconstruction for breast cancer. Surgery 2002;131:S324-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakajima H, Sakaguchi K, Mizuta N, et al. Video-assisted total glandectomy and immediate reconstruction for breast cancer. Biomed Pharmacother 2002;56:205s-8s. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Casella D, Cassetti D, Marcasciano M, et al. Double Asymmetric Circular Incision, a New Skin-Sparing Mastectomy Technique: Results and Outcomes of the First 46 Procedures. Plast Reconstr Surg 2023;151:384e-7e. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krohn IT, Cooper DR, Bassett JG. Radical mastectomy: thick vs thin skin flaps. Arch Surg 1982;117:760-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beer GM, Varga Z, Budi S, et al. Incidence of the superficial fascia and its relevance in skin-sparing mastectomy. Cancer 2002;94:1619-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cao D, Tsangaris TN, Kouprina N, et al. The superficial margin of the skin-sparing mastectomy for breast carcinoma: factors predicting involvement and efficacy of additional margin sampling. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:1330-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O'Connell RL, Rusby JE. Anatomy relevant to conservative mastectomy. Gland Surg 2015;4:476-83. [PubMed]

- Garcia-Etienne CA, Cody Iii HS 3rd, Disa JJ, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy: initial experience at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and a comprehensive review of literature. Breast J 2009;15:440-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salibian AH, Harness JK, Mowlds DS. Inframammary approach to nipple-areola-sparing mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2013;132:700e-8e. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Proano E, Perbeck LG. Influence of the site of skin incision on the circulation in the nipple-areola complex after subcutaneous mastectomy in breast cancer. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 1996;30:195-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blondeel PN, Hijjawi J, Depypere H, et al. Shaping the breast in aesthetic and reconstructive breast surgery: an easy three-step principle. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;123:455-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones C, Lancaster R. Evolution of Operative Technique for Mastectomy. Surg Clin North Am 2018;98:835-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lipshy KA, Neifeld JP, Boyle RM, et al. Complications of mastectomy and their relationship to biopsy technique. Ann Surg Oncol 1996;3:290-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sbitany H, Wang F, Peled AW, et al. Immediate implant-based breast reconstruction following total skin-sparing mastectomy: defining the risk of preoperative and postoperative radiation therapy for surgical outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg 2014;134:396-404. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carlson GW. Risk of recurrence after treatment of early breast cancer with skin-sparing mastectomy: two editorial perspectives. Ann Surg Oncol 1998;5:101-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kroll SS, Coffey JA Jr, Winn RJ, et al. A comparison of factors affecting aesthetic outcomes of TRAM flap breast reconstructions. Plast Reconstr Surg 1995;96:860-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kroll SS. The value of skin-sparing mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol 1998;5:660-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- González EG, Morgado CC, Noblía C, et al. Reconstrucción mamaria post mastectomía. Rol actual enel tratamiento del cáncer de mama. Prens Méd Argent 2000;87:578-94.

- Filip CI, Jecan CR, Raducu L, et al. Immediate Versus Delayed Breast Reconstruction for Postmastectomy Patients. Controversies and Solutions. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2017;112:378-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matar DY, Wu M, Haug V, et al. Surgical complications in immediate and delayed breast reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2022;75:4085-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Urban C, Rietjens M. editors. Oncoplastic and Reconstructive Breast Surgery. Milano: Springer Milan; 2013.

- Kronowitz SJ, Kuerer HM. Advances and surgical decision-making for breast reconstruction. Cancer 2006;107:893-907. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quinn TT, Miller GS, Rostek M, et al. Prosthetic breast reconstruction: indications and update. Gland Surg 2016;5:174-86. [PubMed]

- Seth I, Bulloch G, Jennings M, et al. The effect of chemotherapy on the complication rates of breast reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2023;82:186-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mannu GS, Navi A, Morgan A, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy before mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction may predict post-mastectomy radiotherapy, reduce delayed complications and improve the choice of reconstruction. Int J Surg 2012;10:259-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kronowitz SJ, Robb GL. Breast reconstruction with postmastectomy radiation therapy: current issues. Plast Reconstr Surg 2004;114:950-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eifel P, Axelson JA, Costa J, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: adjuvant therapy for breast cancer, November 1-3, 2000. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:979-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kronowitz SJ, Hunt KK, Kuerer HM, et al. Delayed-immediate breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2004;113:1617-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Seth I, Xie Y, Lim B, Rozen WM, Hunter-Smith DJ. Defining skin-sparing mastectomy surgical techniques: a narrative review. Ann Breast Surg 2024;8:20.