Impact of the National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers reconstruction standard on reconstruction rates at Commission on Cancer centers with breast center accreditation

Highlight box

Key findings

• National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers (NAPBC) accreditation is associated with increased rates of reconstruction and fewer disparities by race, insurance status and facility type.

What is known and what is new?

• In 2011, the NAPBC enacted a standard requiring centers to provide a referral to a reconstructive surgeon for eligible breast cancer patients undergoing mastectomy.

• Since the release of this statement, breast reconstruction rates have increased at NAPBC accredited sites as well as at low volume and rural breast cancer sites.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• These findings are significant because there have been no studies that have examined the impact of the NAPBC reconstruction standard at Commission on Cancer centers on breast reconstruction rates. Our study shows that heavily resourced sites with NAPBC accreditation can provide high rates of reconstruction even if they are community-based sites with lower volumes.

Introduction

In 1998, the United States Congress passed the Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act, which mandated that insurance companies cover reconstruction after mastectomy. Since this Act was passed, reconstruction rates have steadily increased. A study utilizing the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data reported a reconstruction rate of 15.9% in 1998 and 16.2% in 2002 (1). A study by the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development showed reconstruction rates of 29.2% in 2007 (2). A study from our group utilizing the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) showed reconstruction rates of 26% in 2007 (3). In contrast, a study utilizing the MarketScan database demonstrated reconstruction rates of 63% in 2007 and 75% in 2014 (4). Another single institution study that reviewed the number of patients that had undergone breast reconstruction between 2010 and 2015 found that 73.6% of their patient population received breast reconstruction (5). The 2020 plastic surgery statistics report showed that approximately 137,000 patients had breast reconstructive surgery and that there has been a 75% increase in breast reconstruction surgery from 2000 to 2020 (6). These studies demonstrate not only the increasing rates of breast reconstruction, but the variability in reconstruction rates across the country.

The Commission on Cancer (CoC) is a consortium of over 1,500 cancer centers across the United States led by the American College of Surgeons Cancer Program. Some CoC centers also have accreditation through the National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers (NAPBC), a separate quality program of the American College of Surgeons that started in 2008. NAPBC accreditation requires the fulfillment of standards that pertain to breast disease care delivery. One of the NAPBC standards states that breast reconstruction should be provided or referred for patients undergoing mastectomy. In 2011, the NAPBC added a further provision to this reconstruction standard that required that all “appropriate mastectomy patients should be offered a preoperative referral to a reconstructive/plastic surgeon”. This reconstruction standard is not part of CoC accreditation. The purpose of this study was to examine how NAPBC accreditation and the reconstruction standard impacted breast reconstruction rates at CoC sites with and without breast center accreditation. Furthermore, we examined breast reconstruction rates amongst groups of patients who typically have lower rates of reconstruction at CoC-NAPBC versus CoC-noNAPBC sites. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://abs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/abs-23-3/rc).

Methods

Study design and participants

This retrospective observational cohort study included women with the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage 0–III breast cancer diagnosed from 2009 to 2017 who underwent a mastectomy at a CoC site. Patients who underwent a unilateral or bilateral mastectomy, simple mastectomy, modified radical or radical mastectomy, and/or nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM) were classified as undergoing a “mastectomy”. Patients who underwent either implant or tissue-based reconstruction were categorized as undergoing reconstruction, oncoplastic procedures were not included in the reconstructed cohort because the NCDB does not collect oncoplastic procedures. Patients who underwent implant and tissue-based reconstruction were categorized together because of concerns regarding the accuracy and completeness of the data on type of reconstruction in the NCDB. Women <40, >80 years old and with Stage IV breast cancer were excluded from the study. Patients that were <40 years old were excluded from the study because the NCDB suppresses facility characteristics for women <40 years old to ensure privacy of the centers.

Variables

The following patient variables were examined in a categorical fashion: year of diagnosis, age, race, type of insurance, household income, and comorbidity index. Facility factors annual case volume [0–100 (low), 101–250 (mid), >250 (high)], regional location (based on census regions), facility area (metro, urban, rural, unknown) and presence of NAPBC accreditation and year of accreditation (7). Facilities that have teaching or research programs were categorized as academic/teaching facilities.

Data source

We utilized the NCDB which collects data from over 70% of newly diagnosed cancer cases at any of the 1,500 CoC facilities across the United States. We utilized a participant user file which included the years 2004 to 2017 and includes whether the CoC site has received NAPBC accreditation and the year of accreditation. All data within the NCDB are deidentified and compliant with the privacy requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Our institutional review board (IRB) deemed approval was not required for this study because no patient, provider, or hospital identifiers were examined, no protected health information was reviewed, and this was a retrospective analysis. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics, frequency with percentage or mean with standard deviation were used to compare patients with and without reconstruction. Chi-square and independent samples t-tests were used to assess differences between groups. Trends over time were assessed using the Cochran-Armitage test for trend. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to identify factors associated with receiving reconstruction and to identify potential confounders. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported. Patient age, race, socioeconomic factors, geographic factors, and facility characteristics were compared and evaluated as predictors of breast reconstruction. The first CoC centers to receive NAPBC accreditation were accredited in 2008. We compared breast reconstruction rates at CoC-NAPBC sites three years before and after the year these sites were accredited. This analysis was performed for centers accredited in the years 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015. All statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) with two-tailed tests and a significance level of P<0.05.

Results

Demographics of the patient cohort

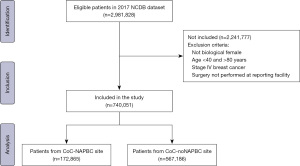

Of 2,981,828 patients included in the 2017 NCDB dataset, 740,051 patients were included in the study after excluding patients that were <40, >80 years old, had stage IV breast cancer, or did not have surgery performed at the reporting facility. Of 172,865 patients treated with mastectomy at 451 CoC-NAPBC sites, 88,436 (51.2%) had reconstruction. Of 567,186 patients treated with mastectomy at 1,344 CoC-noNAPBC sites, 191,295 (33.7%) had reconstruction. Table 1 lists demographic characteristics between the patients treated at CoC-NAPBC and CoC-noNAPBC facilities. Figure 1 shows the selection criteria for the patient cohort.

Table 1

| Characteristics | CoC-noNAPBC, n (%) | CoC-NAPBC, n (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients, N | 567,186 | 172,865 | |

| Year of diagnosis | <0.0001 | ||

| <2009 | 215,026 (37.9) | 226 (0.1) | |

| 2009–2012 | 173,867 (30.7) | 53,990 (31.2) | |

| >2012 | 178,293 (31.4) | 118,649 (68.6) | |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 59±11 | 58±11 | <0.0001 |

| Age, years | <0.0001 | ||

| 40–54 | 219,788 (38.8) | 71,637 (41.4) | |

| 55–64 | 161,175 (28.4) | 50,074 (29.0) | |

| 65–80 | 186,223 (32.8) | 51,154 (29.6) | |

| Race | <0.0001 | ||

| White | 442,216 (78.0) | 132,386 (76.6) | |

| Black | 61,082 (10.8) | 21,913 (12.7) | |

| Hispanic | 32,438 (5.7) | 8,299 (4.8) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 22,010 (3.9) | 7,778 (4.5) | |

| Other/unknown | 9,440 (1.7) | 2,489 (1.4) | |

| Insurance | <0.0001 | ||

| Private | 326,003 (57.5) | 106,950 (61.9) | |

| Medicare | 178,052 (31.4) | 49,033 (28.4) | |

| Medicaid | 37,115 (6.5) | 10,537 (6.1) | |

| Other government | 5,622 (1.0) | 1,985 (1.2) | |

| Unknown | 8,324 (1.5) | 1,393 (0.8) | |

| Uninsured | 12,070 (2.1) | 2,967 (1.7) | |

| Medicaid expansion Jan 1st 2014 (N=519,842) | <0.0001 | ||

| No | 229,374 (58.3) | 69,141 (54.8) | |

| Yes | 164,358 (41.7) | 56,969 (45.2) | |

| Facility area | <0.0001 | ||

| Metro | 474,424 (83.7) | 149,657 (86.6) | |

| Urban | 68,611 (12.1) | 16,786 (9.7) | |

| Rural | 8,943 (1.6) | 2,521 (1.5) | |

| Unknown | 15,208 (2.7) | 3,901 (2.3) | |

| Annual facility volume | <0.0001 | ||

| Low [0–100] | 87,309 (15.4) | 9,998 (5.8) | |

| Mid [101–250] | 198,378 (35.0) | 62,564 (36.2) | |

| High [>250] | 281,499 (49.6) | 100,303 (58.0) | |

| Academic/research facility type | <0.0001 | ||

| No | 396,375 (69.9) | 109,037 (63.1) | |

| Yes | 170,811 (30.1) | 63,828 (36.9) | |

| Facility location | <0.0001 | ||

| New England | 24,429 (4.3) | 9,301 (5.4) | |

| Middle Atlantic | 75,570 (13.3) | 29,409 (17.0) | |

| South Atlantic | 119,928 (21.1) | 51,269 (29.7) | |

| East North Central | 88,011 (15.5) | 36,103 (20.9) | |

| East South Central | 49,049 (8.7) | 6,926 (4.0) | |

| West North Central | 51,425 (9.1) | 9,783 (5.7) | |

| West South Central | 57,680 (10.2) | 9,876 (5.7) | |

| Mountain | 26,274 (4.6) | 8,415 (4.9) | |

| Pacific | 74,820 (13.2) | 11,783 (6.8) | |

| Reconstruction | − | ||

| No | 375,891 (66.3) | 84,429 (48.8) | |

| Yes | 191,295 (33.7) | 88,436 (51.2) | |

CoC, Commission on Cancer; NAPBC, National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers; SD, standard deviation.

Breast reconstruction rates at CoC sites with and without NAPBC accreditation

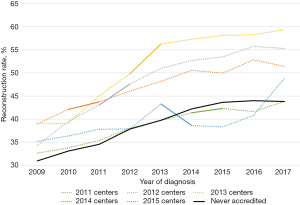

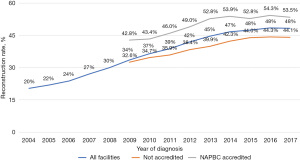

Figure 2 shows the reconstruction rates at CoC-NAPBC versus CoC-noNAPBC sites from 2004 to 2017. Of note, NAPBC accreditation did not start until 2009. There was a significant increase in reconstruction rates at both CoC-NAPBC and CoC-noNAPBC sites, but a higher proportion of patients underwent reconstruction at CoC-NAPBC sites than CoC-noNAPBC sites, 53.5% vs. 44.1% respectively in 2017. Figure 3 shows the reconstruction rates by year of accreditation. This graph shows that there was a significant increase in reconstruction rates after the year of accreditation for sites that were accredited in 2011–2013 but rates remained relatively stable for 2014–2016. Reconstruction rates were examined prior to and after NAPBC accreditation stratified by year of accreditation (Table 2). There was a significant change in reconstruction rates from before and after NAPBC accreditation for each year from 2010 to 2015, but the numbers varied by year of accreditation. For example, for those centers accredited in 2010, 34.0% of CoC-NAPBC centers performed reconstruction 3 years prior to NAPBC accreditation compared to 48.1% three years after accreditation for an absolute difference of 14.1%. In contrast, for those centers accredited in 2015, 39.8% performed reconstruction prior to NAPBC accreditation compared to 42.7% after accreditation, for an absolute difference of only 2.9%. However, the absolute difference in reconstruction rates increased narrowed starting in 2014 suggesting that NAPBC accreditation’s impact on reconstruction rates was short-lived. A multivariable analysis adjusting for patient, socioeconomic and facility factors showed that NAPBC accreditation was associated with an OR 1.32 (95% CI: 1.30–1.34) increased odds of undergoing reconstruction compared to not undergoing NAPBC accreditation (Table S1).

Table 2

| Variables | 2010 centers | 2011 centers | 2012 centers | 2013 centers | 2014 centers | 2015 centers† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total centers | 94 | 87 | 48 | 40 | 22 | 30 |

| Total patients | 53,823 | 43,849 | 24,487 | 15,447 | 7,795 | 12,456 |

| Before accreditation (%) | 34 | 40.6 | 38.9 | 44.8 | 39.6 | 39.8 |

| After accreditation (%) | 48.1 | 48.3 | 52.4 | 57.9 | 42.7 | 42.7 |

| Absolute change (%) | 14.1 | 7.7 | 13.5 | 13.1 | 3.1 | 2.9 |

| P value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0215 | 0.0117 |

†, only 2 years of data after accreditation are available. NAPBC, National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers.

Breast reconstruction rates stratified by race, patient age and insurance status

Comparing CoC-NAPBC to CoC-noNAPBC centers in 2016–2017, more Black (38.5% vs. 24.8%), Hispanic (43.1% vs. 31.3%) and Asian Americans (35.5% vs. 26.7%) underwent reconstruction. Most women that underwent reconstruction were 40–54 years old at both CoC-NAPBC (59.8%) and CoC-noNAPBC centers (46.6%), however a greater percentage of patients 65–80 years old underwent reconstruction at CoC-NAPBC centers (22.9%) compared to CoC-noNAPBC centers (13.5%). Similarly, more Medicaid patients (35.6% vs. 22.5%) underwent reconstruction at CoC-NAPBC sites compared to CoC-noNAPBC sites (Table 3). A multivariate analysis adjusting for patient, socioeconomic and facility factors showed that NAPBC accreditation was associated with a higher likelihood of undergoing reconstruction amongst all racial groups (Table S2). Patients that were 40–54 years old were more likely to undergo reconstruction for all racial groups.

Table 3

| Variables | CoC-noNAPBC, n (%) | CoC-NAPBC, n (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| <2009 | 53,033 (24.7) | 49 (21.7) | 0.2986 |

| 2009–2012 | 59,155 (34.0) | 23,632 (43.8) | <0.0001 |

| >2012 | 66,936 (37.5) | 53,674 (45.2) | <0.0001 |

| Age, years | |||

| 40–54 | 102,472 (46.6) | 42,839 (59.8) | <0.0001 |

| 55–64 | 51,538 (32.0) | 22,789 (45.5) | <0.0001 |

| 65–80 | 25,114 (13.5) | 11,727 (22.9) | <0.0001 |

| Race | |||

| White | 144,887 (32.8) | 61,530 (46.5) | <0.0001 |

| Black | 15,144 (24.8) | 8,430 (38.5) | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic | 10,143 (31.3) | 3,573 (43.1) | <0.0001 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 5,871 (26.7) | 2,760 (35.5) | <0.0001 |

| Other/unknown | 3,079 (32.6) | 1,062 (42.7) | <0.0001 |

| Insurance | |||

| Private | 139,907 (42.9) | 59,543 (55.7) | <0.0001 |

| Medicare | 25,379 (14.3) | 11,629 (23.7) | <0.0001 |

| Medicaid | 8,345 (22.5) | 3,748 (35.6) | <0.0001 |

| Other government | 1,972 (35.1) | 981 (49.4) | <0.0001 |

| Unknown | 1,605 (19.3) | 568 (40.8) | <0.0001 |

| Uninsured | 1,916 (15.9) | 886 (29.9) | <0.0001 |

| Income | |||

| <$38,000 | 16,889 (20.0) | 6,433 (31.7) | <0.0001 |

| $38,000–$62,999 | 69,692 (27.5) | 25,468 (39.1) | <0.0001 |

| ≥$63,000 | 76,240 (41.5) | 35,342 (53.1) | <0.0001 |

| Unknown | 16,303 (36.0) | 10,112 (48.4) | <0.0001 |

| Facility area | |||

| Metro | 156,704 (33.0) | 68,616 (45.8) | <0.0001 |

| Urban | 15,203 (22.2) | 6,010 (35.8) | <0.0001 |

| Rural | 1,707 (19.1) | 774 (30.7) | <0.0001 |

| Unknown | 5,510 (36.2) | 1,955 (50.1) | <0.0001 |

| Annual facility volume | |||

| Low [0–100] | 15,815 (18.1) | 3,121 (31.2) | <0.0001 |

| Mid [101–250] | 51,655 (26.0) | 25,974 (41.5) | <0.0001 |

| High [>250] | 111,654 (39.7) | 48,260 (48.1) | <0.0001 |

| Academic/research facility type | |||

| No | 114,776 (29.0) | 47,414 (43.5) | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 64,348 (37.7) | 29,941 (46.9) | <0.0001 |

| Facility location | |||

| New England | 8,469 (34.7) | 4,599 (49.4) | <0.0001 |

| Middle Atlantic | 30,675 (40.6) | 14,946 (50.8) | <0.0001 |

| South Atlantic | 36,085 (30.1) | 23,460 (45.8) | <0.0001 |

| East North Central | 26,251 (29.8) | 16,345 (45.3) | <0.0001 |

| East South Central | 12,419 (25.3) | 2,884 (41.6) | <0.0001 |

| West North Central | 17,461 (34.0) | 3,930 (40.2) | <0.0001 |

| West South Central | 15,896 (27.6) | 3,687 (37.3) | <0.0001 |

| Mountain | 9,228 (35.1) | 3,453 (41.0) | <0.0001 |

| Pacific | 22,640 (30.3) | 4,051 (34.4) | <0.0001 |

CoC, Commission on Cancer; NAPBC, National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers.

Reconstruction rates at CoC-NAPBC and CoC-noNAPBC sites 2016–2017

Reconstruction rates in 2016–2017 amongst patients treated at CoC-NAPBC and CoC-noNAPBC facilities were stratified by year, patient, and facility factors (Table 3). There was substantial variation in reconstruction rates at rural CoC-NAPBC sites compared to CoC-noNAPBC sites (30.7% vs. 19.1%) and low volume sites (31.2% vs. 18.1%). There is a similar proportion of patients undergoing reconstruction at CoC-NAPBC non-academic/teaching facilities compared to CoC-NAPBC academic/teaching facilities, respectively, 43.5% versus 46.9%. On multivariable analysis, patients treated at community and comprehensive community sites were more likely to undergo reconstruction compared to academic/research sites at CoC-NAPBC sites but not at CoC-noNAPBC sites (Table S3). There was also regional variation in reconstruction rates at CoC-NAPBC sites and CoC-noNAPBC sites such that there was at least a 10% difference in the proportion of patients undergoing reconstruction between CoC-NAPBC and CoC-noNAPBC sites except for the Mountain, Pacific and West North Central regions of the country.

Discussion

In this NCDB study, we show that reconstruction rates after mastectomy are increasing for both CoC-NAPBC and CoC-noNAPBC sites, but rates remain higher at CoC-NAPBC sites, 53.5% vs. 44.1% in 2017, the most recent year of the study. These rates are substantially higher than our previous NCDB study which reported a 26% reconstruction rate in 2007 (3).

Our data show that NAPBC accreditation is having an impact on reconstruction rates, but it is short-lived. The absolute difference in reconstruction rates before and after accreditation was larger in the early years of NAPBC accreditation [2010–2013] but decreased in 2014–2015. Shortly after the NAPBC required that reconstruction be “offered” to mastectomy patients, the reconstruction rates took a jump from approximately 7% to 13.5% from 2011 to 2012, but it is impossible to know if this additional provision to the reconstruction standard was the reason these rates increased. This trend would suggest that NAPBC accreditation may not impact breast reconstruction rates as much now as it did when NAPBC accreditation was a new program. Indeed, breast reconstruction rates have been increasing over the years at both CoC-NAPBC and CoC-noNAPBC sites. At the same time, less CoC centers are undergoing new NAPBC accreditation; in 2010, 94 centers applied for new accreditation compared to 2015 when only 30 centers applied for NAPBC accreditation for the first time so these trends could be impacting our reconstruction numbers. Nonetheless, NAPBC accreditation has been shown to be associated with other quality measures in breast care such as the use of post mastectomy chest wall radiation therapy and higher performance on CoC breast cancer quality measures (8,9). NAPBC accreditation appears to have a positive impact on the quality of breast care, but it is not clear how long this impact lasts and if the impact is evenly distributed at all sites.

Studies have shown that there is an increase in the rate of breast reconstruction as a result of surgeons discussing reconstruction options with patients and providing them with referrals to see a plastic surgeon. One cross-sectional survey study found that women that had a previous knowledge of breast reconstruction were approximately five times more likely to undergo reconstruction (OR 5.805, P=0.26) (10). The study also reported a low overall reconstruction rate of only 20.6%, which was attributed in part to a low referral rate by surgeons. Another study examined the effects of the “Breast Cancer Provider Discussion Law” that was passed in New York State in 2010 and showed that there was an average reconstruction rate of 57% per year compared to national rates ranging from 24% to 42% (11). Another study showed that 41% of women awaiting surgery were willing to reconsider their decision regarding breast reconstructive surgery if their surgical options were properly discussed and they had a better understanding of post reconstruction results (12). This study also showed that only approximately 50% of women have knowledge of breast reconstruction, but the same proportion of women get their information about reconstruction from physicians. All of these studies demonstrate that requiring a surgeon to discuss reconstruction with their patients, as the NAPBC standard stated, can have a large impact on whether patients actually undergo reconstruction or not.

Nonetheless, we cannot be certain that NAPBC accreditation is the only reason that reconstruction rates increased at CoC-NAPBC sites. Reconstruction rates have been increasing at CoC-noNAPBC sites as well. Although the CoC does not have a standard that pertains to breast reconstruction, there could be other factors not included in the NCDB that could account for this increase in reconstruction. Some of these factors would be the increased number and availability of plastic reconstructive surgeons or more plastic surgeons trained in reconstructive techniques. Studies have revealed that patients treated at hospitals with low numbers of plastic surgeons were less likely to undergo breast reconstructive surgery given the inability to meet reconstructive demand (13). The fact that CoC-NAPBC sites have higher reconstruction rates may not be surprising given the fact that CoC-NAPBC sites have more resources for breast patients and focus on providing more specialized breast care for these patients. Presumably, centers would not apply for NAPBC accreditation unless they had resources and programs in place to comply with all required NAPBC standards. Older age has also been associated with lower rates of breast reconstruction for women with breast cancer in previous studies (14,15). Our study found that a majority of women that underwent reconstruction were 40–54 years old at both CoC-NAPBC (59.8%) and CoC-noNAPBC centers (46.6%), however, a greater percentage of patients 65–80 years old underwent reconstruction at CoC-NAPBC centers (22.9%) compared to CoC-noNAPBC centers (13.5%). Given the retrospective design of this study, it is impossible to determine what other factors contribute to higher reconstruction rates over time besides NAPBC accreditation.

Our data do demonstrate fewer racial disparities in reconstruction rates by race and insurance status at CoC-NAPBC sites then CoC-noNAPBC sites. African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians all have higher reconstruction rates at CoC-NAPBC sites than CoC-noNAPBC sites and NAPBC accreditation is an independent predictor of breast reconstruction across all racial groups. Fortunately, all racial groups experienced an increase in breast reconstruction rates, no one group was favored more than another. Hispanics now have reconstruction rates almost equivalent to Whites, 43.1% vs. 46.5%, respectively, in 2016–2017. Nonetheless, African Americans and Asians/Pacific Islanders still have a lower likelihood of undergoing reconstruction compared to Whites and this likelihood has not changed since NAPBC started. Other studies have shown the same disparities. A study conducted from 2003–2007 in Southern California showed reconstruction rates of 26.8% for White patients versus 19.5% for African American and 14.8% for Asian women. African Americans, Hispanics and Asians were less likely to undergo reconstruction than Whites after adjusting for facility and patient factors (2). A study published in 2018 showed that 59% of White patients had breast reconstruction compared to 47% of Hispanic patients, 42% of African American patients, and 41% of Asian/Pacific Islanders (16). Surprisingly, this study also found that African American women with private insurance and living in regions with high access to plastic surgeons have breast reconstruction rates that are still 25% lower than White patients, suggesting that insurance status and geographic access to reconstructive plastic surgeons are not the root cause of racial and ethnic health care disparities for patients seeking breast reconstructive surgery. This study and others underscore the complex nature of the decision to undergo reconstruction.

Breast reconstruction is believed to be part of the complete care for patients diagnosed with breast care. However, despite the Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act, barriers such as insurance coverage previously prevented patients from being able to take advantage of breast reconstructive surgery. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was implemented in 2014 and expanded Medicaid coverage for many patients. Other studies have shown that Medicaid expansion increased the rate of breast reconstruction in patients undergoing mastectomies (17). Our data show that a higher proportion of Medicaid patients undergo reconstruction at CoC-NAPBC sites compared to CoC-noNAPBC sites, but this proportion of patients is still much lower than for patients on private insurance. The impact of Medicaid expansion in 2014 on breast reconstruction rates was reviewed by a study conducted at Loma Linda University (17). This study found that there was a decrease in disparities amongst non-Hispanic black and white breast cancer patients and patients within the lowest education and income quartiles undergoing mastectomy in the years after the Medicaid expansion. Nearly 20 years after the Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act, there are still widespread disparities in reconstruction rates according to insurance type.

Even CoC-NAPBC centers designated as academic/research centers had higher reconstruction rates than CoC-noNAPBC centers, 46.9% versus 37.7%, respectively. Previous studies have found that academic and research institutions complete more breast reconstructive surgery than nonacademic-based centers, given that these institutions have greater access to plastic surgeons (18,19). However, despite the presence of academic and teaching programs, centers with NAPBC accreditation still had higher breast reconstruction rates.

Our study is high volume and broad in scope but has limitations. The NCDB is a retrospective observational dataset, and our data show an association of NAPBC accreditation with breast reconstruction rates but not causation. Although we see some association between NAPBC accreditation and the increase in reconstruction early on, the rates of reconstruction at both CoC-NAPBC and CoC-noNAPBC rates have been increasing over the years. The increased rate of bilateral mastectomies may account for the increased trend in breast reconstruction since bilateral mastectomy patients are more likely to undergo reconstruction (20,21). The NCDB is a large and inclusive database that includes breast cancer cases at CoC facilities from across the United States. However, given that CoC-accredited facilities represent approximately one-third of hospitals nationally, this could limit the generalizability of this NCDB study. Our data only go through 2017 and recent studies have reported a trend of patients opting for no reconstruction and “going flat”. Future studies examining more recent years will demonstrate if this trend is long lasting (22).

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have shown that reconstruction rates continue to increase and that NAPBC accreditation at CoC sites is associated with higher reconstruction rates across different races, facility types, and insurance types. Some racial disparities have been minimized over time, but some remain. Heavily resourced sites with NAPBC accreditation can provide high rates of reconstruction even if they are community-based sites with lower volumes.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://abs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/abs-23-3/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://abs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/abs-23-3/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://abs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/abs-23-3/coif). R.S. is a committee member of the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) Clinical Affairs and Quality Council (CAQC) which is centered around promoting quality improvement in radiation oncology. As a committee member, he contributes to the development and implementation of quality improvement initiatives, guidelines, and standards within the field. L.W. is the Principal Investigator for the University of Wisconsin NCTN NCI LAPs grant which provides funding for phase 2/3 clinical trials in cancer at the University of Wisconsin (federal funding); she is the PI for a clinical trial, investigating tumor margins in breast cancer through a company called Perimeter. She does not take salary support and this is for institution support for the trial; she is a minority stock owner and founder of a technology for intraoperative navigation—Elucent Medical. She owns less than 2% of the company; she is a reviewer for the Department of Defense Era of Hope Grant mechanism and receives a small stipend for time spent on reviewing these grants (federal grants). S.K. reports that as a member and past Chair of NAPBC, he has and had an interest in demonstrating the value of NAPBC accreditation. K.Y. is the Chair of the National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers of the American College of Surgeons. She does not receive any payment for this role. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Agarwal S, Pappas L, Neumayer L, et al. An analysis of immediate postmastectomy breast reconstruction frequency using the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. Breast J 2011;17:352-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kruper L, Holt A, Xu XX, et al. Disparities in reconstruction rates after mastectomy: patterns of care and factors associated with the use of breast reconstruction in Southern California. Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18:2158-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sisco M, Du H, Warner JP, et al. Have we expanded the equitable delivery of postmastectomy breast reconstruction in the new millennium? Evidence from the national cancer data base. J Am Coll Surg 2012;215:658-66; discussion 666. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jagsi R, Jiang J, Momoh AO, et al. Trends and variation in use of breast reconstruction in patients with breast cancer undergoing mastectomy in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:919-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang MM, Warnack E, Joseph KA. Breast Reconstruction in an Underserved Population: A Retrospective Study. Ann Surg Oncol 2019;26:821-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Plastic Surgery Statistics | American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Available online: https://www.plasticsurgery.org/news/plastic-surgery-statistics

- About cancer program categories. American College of Surgeons. Available online: https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/coc/accreditation/categories. Published December 12, 2021. Accessed January 6, 2022.

- Berger ER, Wang CE, Kaufman CS, et al. National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers Demonstrates Improved Compliance with Post-Mastectomy Radiation Therapy Quality Measure. J Am Coll Surg 2017;224:236-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miller ME, Bleicher RJ, Kaufman CS, et al. Impact of Breast Center Accreditation on Compliance with Breast Quality Performance Measures at Commission on Cancer-Accredited Centers. Ann Surg Oncol 2019;26:1202-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ishak A, Yahya MM, Halim AS. Breast Reconstruction After Mastectomy: A Survey of Surgeons' and Patients' Perceptions. Clin Breast Cancer 2018;18:e1011-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fu RH, Baser O, Li L, et al. The Effect of the Breast Cancer Provider Discussion Law on Breast Reconstruction Rates in New York State. Plast Reconstr Surg 2019;144:560-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nair NS, Penumadu P, Yadav P, et al. Awareness and Acceptability of Breast Reconstruction Among Women With Breast Cancer: A Prospective Survey. JCO Glob Oncol 2021;7:253-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bauder AR, Gross CP, Killelea BK, et al. The Relationship Between Geographic Access to Plastic Surgeons and Breast Reconstruction Rates Among Women Undergoing Mastectomy for Cancer. Ann Plast Surg 2017;78:324-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oh DD, Flitcroft K, Brennan ME, et al. Patterns and outcomes of breast reconstruction in older women - A systematic review of the literature. Eur J Surg Oncol 2016;42:604-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gibreel WO, Day CN, Hoskin TL, et al. Mastectomy and Immediate Breast Reconstruction for Cancer in the Elderly: A National Cancer Data Base Study. J Am Coll Surg 2017;224:895-905. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Butler PD, Familusi O, Serletti JM, et al. Influence of race, insurance status, and geographic access to plastic surgeons on immediate breast reconstruction rates. Am J Surg 2018;215:987-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ramalingam K, Ji L, Pairawan S, et al. Improvement in Breast Reconstruction Disparities following Medicaid Expansion under the Affordable Care Act. Ann Surg Oncol 2021;28:5558-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siegel E, Tseng J, Giuliano A, et al. Treatment at Academic Centers Increases Likelihood of Reconstruction After Mastectomy for Breast Cancer Patients. J Surg Res 2020;247:156-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Retrouvey H, Solaja O, Gagliardi AR, Webster F, Zhong T. Barriers of Access to Breast Reconstruction: A Systematic Review. Plast Reconstr Surg 2019;143:465e-476e. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barnow A, Canfield T, Liao R, et al. Breast Reconstruction Among Commercially Insured Women With Breast Cancer in the United States. Ann Plast Surg 2018;81:220-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hershman DL, Richards CA, Kalinsky K, et al. Influence of health insurance, hospital factors and physician volume on receipt of immediate post-mastectomy reconstruction in women with invasive and non-invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012;136:535-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baker JL, Dizon DS, Wenziger CM, et al. "Going Flat" After Mastectomy: Patient-Reported Outcomes by Online Survey. Ann Surg Oncol 2021;28:2493-505. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Nicholson K, Kuchta K, Bleicher R, Stevens R, Dietz J, Wilke L, Kurtzman S, Sarantou T, Yao K. Impact of the National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers reconstruction standard on reconstruction rates at Commission on Cancer centers with breast center accreditation. Ann Breast Surg 2024;8:14.