A case report of borderline phyllodes tumor: navigating the complexities of rare spindle cell neoplasms

Highlight box

Key findings

• Borderline phyllodes tumor is a nuanced, histology-based diagnosis that may not be confirmed until final excisional biopsy is obtained.

What is known and what is new?

• Borderline phyllodes tumors are rare, but can cause significant morbidity for patients. Preliminary diagnosis may differ significantly from the final pathology, and surgeons should be aware of the limitations of core needle biopsy in diagnosing these lesions.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Clinicians should be aware of the pitfalls one may encounter when managing a patient with a fibrous mass, and the oncologic management of phyllodes tumors.

Introduction

Spindle cell lesions of the breast (BSCL) encompass a wide array of both benign and malignant masses. Due to the heterogeneous nature of lesions, and similar pathologic and radiologic characteristics of both benign and malignant lesions, it can be challenging to obtain a conclusive diagnosis from core needle biopsy. It is necessary to evaluate the morphology of these lesions by assessing borders, mitotic rate, and atypia, as well as employing techniques such as immunohistochemistry, to categorize them as low grade (benign) or high grade (malignant). Low grade lesions include fibroadenoma, hamartoma, pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH), and benign or borderline phyllodes. High grade or malignant lesions such as high-grade sarcoma, melanoma, high grade spindle cell metaplastic carcinoma, and malignant phyllodes differ significantly in guidelines for resection and treatment. We present the case of a rapidly growing borderline phyllodes tumor with evolution concerning for malignancy and the difficulties encountered in diagnosing BSCL. We present this article in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://abs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/abs-24-45/rc).

Case presentation

The patient was a 38-year-old female who presented to the breast clinic for screening mammogram with the complaint of a left breast mass that had been rapidly growing for six to seven months (Figure 1). The patient denied breast pain or nipple discharge but was bothered by the extra weight and bulkiness of her left breast. Her medical history was significant for history of schizophrenia, hypertension, and 12 pack-years of smoking. She endorsed a family history of multiple cancers including breast cancer. Physical exam revealed a significantly enlarged left breast with a palpable mass. No skin changes, ulceration, nipple discharge, or lymphadenopathy were noted.

After physical exam screening mammogram was converted to diagnostic mammogram, and concurrent breast ultrasound was also performed. Imaging revealed multiple masses in both breasts. The left breast mammogram was significant for a very large 22 cm mixed density mass occupying the central and lateral breast as well as a 3-cm circumscribed mass in the lower inner quadrant. The accompanying left breast ultrasound reported this large mass to be up to 30 cm with a complex fluid component and multiple masses at the 9:00 position. The right breast mammogram was significant for multiple small circumscribed masses with the largest measuring 1.5 cm in the posterior upper inner quadrant. Right breast ultrasound confirmed this 1.3 cm solid mass at 2:00, 9 cm from the nipple, as well as the adjacent circumscribed masses (Figure 2).

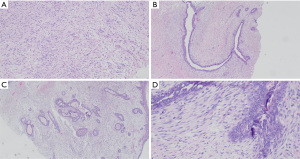

Bilateral core needle biopsies were performed of the largest masses in each breast. In the left breast, core biopsies and fluid aspirate were collected from the dominant fluid-filled mass. In the right breast, the largest 1.3 cm solid mass at 2:00 was sampled. Biopsies from both breasts were consistent with spindle cell neoplasm. Slide review and immunostaining demonstrated the right breast lesion was positive for smooth muscle actin (SMA), and negative for pancytokeratin and S100. The large left breast mass was positive for CD34, BCL1, beta-catenin, and negative for pancytokeratin and S100. Diagnosis of benign fibroepithelial lesions was favored, however other spindle cell proliferations such as low-grade myofibroblastic sarcoma, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) could not be excluded. Cytology from needle aspiration of the large left breast mass demonstrated scattered squamous cells, acute inflammatory cells, and squamous debris without evidence of malignancy. The pathologist noted that on core biopsy, cells from both breasts were morphologically similar, but more sparsely distributed in the right breast lesion than in the left (Figure 3). Additional core biopsies were then collected from other smaller lesions in each breast, which revealed fibroadenoma in the right breast at the 11:00 position and fibroadenomatoid changes in the left breast at the 9:00 position.

Based on the pathology findings of bilateral spindle cell lesions with similar morphologies, and inability to definitively rule out malignancy with core biopsies alone, the patient was scheduled for excisional biopsy of the largest 1.3 cm right breast mass, and resection of the dominant left breast mass. The patient requested breast conserving therapy, and ultimately underwent left breast partial mastectomy of the large mass (Figure 4) with oncoplastic closure (Figure 5), and right breast lumpectomy of the spindle cell lesion using needle localization. Final surgical pathology demonstrated borderline phyllodes tumor in the left breast, and fibroadenoma in the right breast. Pathology of the borderline phyllodes tumor noted “florid ductal hyperplasia, prominent stromal overgrowth as well as cystic degeneration centrally and areas of necrosis.” The patient was extensively counseled on the risk of recurrence associated with her diagnosis and scheduled for a postoperative mammogram in six months. At the post-operative follow-up visit her incisions were healing appropriately and the patient was satisfied with the result.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

Phyllodes tumors are rare fibroepithelial lesions that account for 0.3–0.9% of all diagnosed breast lesions, and only 2–3% of all fibroepithelial lesions (1,2). While rare, proper diagnosis and treatment of these lesions is critical for preventing their malignant spread. Phyllodes tumors are categorized into 3 groups according to their pathologic features– benign, borderline, and malignant. Malignant lesions are characterized by greater cellular atypia, mitotic rate, necrosis, and stromal overgrowth (3). Definitive diagnosis is based on histopathological findings, in which benign phyllodes tumors show minimal atypia and mitotic index of <4/10 HPF, and borderline phyllodes tumors show greater atypia and mitotic index of 5–9/10 HPF (4). Greater stromal cellularity and more extensive areas of necrosis are typical of malignant lesions. Local recurrence rates for phyllodes tumors also vary according to group– benign lesions have 3.6–8% recurrence rate, borderline lesions have 14% recurrence rate, and malignant lesions have 30–42% recurrence rate (5).

Accurate clinical and pathological diagnoses of breast spindle cell lesions (BSCL) are critical for determining appropriate management. The main difficulty lies in the significant morphological overlap between benign and malignant spindle cell lesions on pathology. While evaluating the lesions pathologically, attention must be paid to morphology, borders, cellular atypia, and growth patterns. BSCLs are categorized into two groups– low-grade (non-atypical), and high-grade (malignant) lesions. Low-grade lesions include PASH, spindle cell lipoma, hamartoma, and fibroadenoma. High grade lesions include phyllodes tumor, metastatic malignant spindle cell lesions, melanomas, and sarcomas.

One challenge in the characterization of bland-appearing lesions is the differentiation of fibromatosis-like metastatic breast carcinoma (MBC) from other bland lesions. Cytological features such as minimal nuclear pleomorphism and low mitotic rate are shared between typical bland lesions such as fibroadenomas and fibromatosis-like MBC (6). As expected, the metastatic potential and therefore management of these types of lesions are considerably different, making their proper diagnosis paramount for providing appropriate care.

In the clinical setting, diagnosis is further complicated by the inherent limitations of radiology and tissue sampling in differentiating classes of spindle cell lesions. Many lesions appear similarly in breast radiology, making pre-operative needle biopsy essential. In a sample of 83 women ultimately diagnosed with fibroadenoma or phyllodes tumor, Gatta et al. demonstrated a near overlap in ultrasound and mammographic parameters of the two pathologies (such as size, shape, echogenicity, and structure) as well as an absence of pathognomonic features differentiating them (7). They concluded core needle biopsy was the only reliable way to differentiate the pathologies prior to excision. However, even biopsy is inherently limited in its ability to characterize the overall architecture of the mass, especially in heterogeneous lesions. Notably, this study did not include the intermediate phenotype of borderline phyllodes in its analysis. One could postulate that definitive diagnosis may be even more limited in borderline cases such as this.

In this patient’s case, the pathologist noted that both the fibroadenoma and the borderline phyllodes tumor had similar morphologies on core biopsy. Both samples also shared significant overlap in immunostaining profiles. As expected, tissue from the borderline phyllodes tumor was noted to have greater cell density than the fibroadenoma. However, cytology from needle aspiration of the borderline phyllodes tumor was initially deemed benign, despite final pathology proving otherwise. This patient presented with multiple bilateral masses of unknown significance. Only total excision of one mass from each breast was adequate to reliably diagnose borderline phyllodes tumor in a background of multiple fibroadenomas.

Treatment of borderline and malignant phyllodes tumors consists of wide local excision of the mass without axillary staging, and postoperative surveillance. Surgical resection with margins of at least 1 cm is associated with lower risk of local recurrence. Due to the high risk of local recurrence in borderline and malignant phyllodes tumors, guidelines recommend surveillance ultrasound every 6 months for the first two years after resection, followed by annual ultrasounds through five years. Adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) is sometimes offered, especially in cases of local recurrence, however there are no prospective randomized controlled trials to date that support the practice (8). A recent meta-analysis of 807 patients with borderline phyllodes tumor demonstrated no significant difference in recurrence rate between patients who received adjuvant RT and those who did not, however only 25 patients in the sample were treated with adjuvant RT (9). Similarly, there is no evidence to date supporting the use of hormone therapy or chemotherapy for phyllodes tumors. In cases of benign phyllodes, clinical follow-up is recommended for three years after diagnosis (9).

Conclusions

Our patient was ultimately diagnosed with a borderline phyllodes tumor after presenting with multiple bilateral breast masses. She underwent wide local excision of the lesion without axillary staging, and surgical incisions were well-healed on follow-up examination. In accordance with National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines (9), she will continue surveillance and clinical follow-up for the next five years with bilateral breast ultrasound and mammograms. Given the rarity of phyllodes tumors in breast pathology, it is imperative that clinicians understand the nuances of diagnosing these tumors, and that we continue to make strides in histopathologic diagnosis to accurately distinguish these malignant lesions from the multitude of spindle cell tumors encountered by the clinician.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their gratitude to Dr. George Turi, Department of Pathology, for sharing his expertise and providing the histology images used in this paper.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://abs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/abs-24-45/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://abs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/abs-24-45/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://abs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/abs-24-45/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement:

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Rowell MD, Perry RR, Hsiu JG, et al. Phyllodes tumors. Am J Surg 1993;165:376-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou ZR, Wang CC, Yang ZZ, et al. Phyllodes tumors of the breast: diagnosis, treatment and prognostic factors related to recurrence. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:3361-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rakha EA, Brogi E, Castellano I, et al. Spindle cell lesions of the breast: a diagnostic approach. Virchows Arch 2022;480:127-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lerwill MF, Lee AHS, Tan PH. Fibroepithelial tumours of the breast-a review. Virchows Arch 2022;480:45-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peneş NO, Pop AL, Borş RG, et al. Large borderline phyllodes breast tumor related to histopathology, diagnosis, and treatment management - case report. Rom J Morphol Embryol 2021;62:283-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pham KH, Nguyen CV, Do TA, et al. Fibromatosis-Like Metaplastic Carcinoma: A Triple-Negative Breast Cancer with Clinically Indolent Behavior. Case Rep Oncol 2022;15:816-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gatta G, Iaselli F, Parlato V, et al. Differential diagnosis between fibroadenoma, giant fibroadenoma and phyllodes tumour: sonographic features and core needle biopsy. Radiol Med 2011;116:905-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu CY, Huang TW, Tam KW. Management of phyllodes tumor: A systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world evidence. Int J Surg 2022;107:106969. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) for Phyllodes Tumor (V.4.2024). Available online: https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1419. Accessed August 5, 2024.

Cite this article as: Chilukuri S, Varney P, Huang L, Ott-Young A, Hodyl C. A case report of borderline phyllodes tumor: navigating the complexities of rare spindle cell neoplasms. Ann Breast Surg 2025;9:13.